The rapid rise in consumer adoption of ad blocking software is threatening the traditional advertising model for publishers. For some, it seems like a topsy-turvy world where none of the old assumptions or the old rules apply.

The rapid rise in consumer adoption of ad blocking software is threatening the traditional advertising model for publishers. For some, it seems like a topsy-turvy world where none of the old assumptions or the old rules apply.

But author and MarComm über-thought leader Gord Hotchkiss reminds us that the consumer behaviors we are witnesses are as old as the hills.

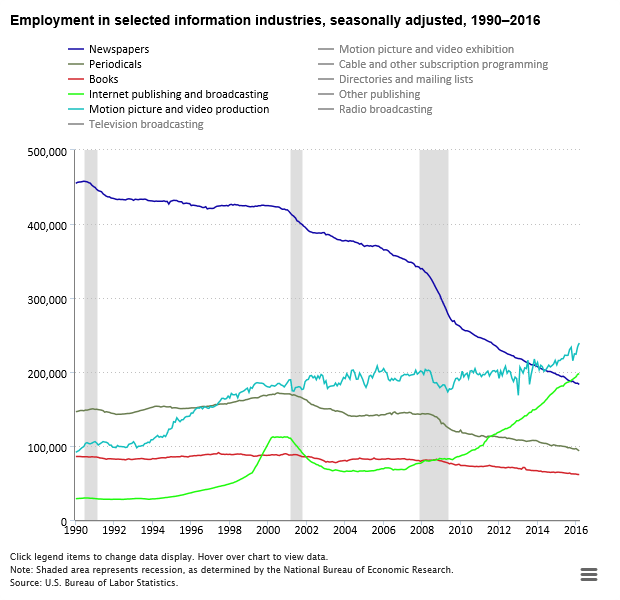

In a recent MediaPost column titled “Why Our Brains Are Blocking Ads,” Hotchkiss points out that the environment for online ads is vastly different from the environment where traditional advertising flourished for decades – primarily in magazines, newspapers and television.

He notes that in the past, the majority of people’s interaction with advertising was done while our brains were in “idling” mode – meaning that they had no specific task at hand. Instead, people were looking for something to capture their attention within a TV program, a newspaper or magazine article.

Hotchkiss contends that in such an environment, the brain is in an “accepting” state and thus is more open to advertising messages:

“We were looking for something interesting, we were primed to be in a positive frame of mind, and our brains could easily handle the contextual switches required to consider an ad and its message.”

Contrast this to the delivery of most digital advertising in today’s world, which is happening when people are in more of a “foraging” mode – involved in a task to find information and answers with our attention focused on that task.

In such an environment, advertising isn’t only a distraction; often, it’s a source of frustration. As Hotchkiss notes:

“The reason we’re blocking [digital] ads is that in the context those ads are being delivered, irrelevant ads are – quite literally – painful. Even relevant ads have a very high threshold to get over.”

Hotchkiss concludes that the rapid rise of ad blocking adoption isn’t about the technology per se. It has to do with the hardwiring of our brains. New technologies haven’t caused fundamental changes in human behavior – they’ve simply enabled new behaviors that weren’t an option before.

As is becoming increasingly obvious, the implications for the advertising business are huge: Ad blocking software is projected to lower digital ad revenues by more than $40 billion in 2016 alone, according to estimates by digital data research firm eMarketer.

As is becoming increasingly obvious, the implications for the advertising business are huge: Ad blocking software is projected to lower digital ad revenues by more than $40 billion in 2016 alone, according to estimates by digital data research firm eMarketer.

Looking back on it, actually it seems like it was all so inevitable.