This past week, Forbes magazine published a feature article authored by its senior education editor, Susan Adams, concerning a $12 billion company that’s benefited mightily from the distance learning measures hastily put in place for secondary and college-level students in the wave of the coronavirus pandemic lockdowns.

This past week, Forbes magazine published a feature article authored by its senior education editor, Susan Adams, concerning a $12 billion company that’s benefited mightily from the distance learning measures hastily put in place for secondary and college-level students in the wave of the coronavirus pandemic lockdowns.

The company in question is Chegg, an education technology firm which offers a $14.95 monthly subscription that provides a lifeline for students who are looking for answers to exam questions.

Headquartered in California, Chegg actually looks more like a company based in India, where it accesses a stable of more than 70,000 people with advanced science, math, engineering and IT degrees. These freelancers are available online continuously, supplying subscribers from around the world with step-by-step answers to their test-related questions. And the answers are typically provided in a matter of mere minutes.

Reportedly, Chegg’s database contains answers on some 46 million textbook and exam question topics, and it’s the driving force behind the company’s Chegg Study subscription service.

Chegg Study is also the main revenue stream of the company — by far. Other services such as resources for improving writing and math skills as well as bibliography-creation software seem more like window-dressing.

It brings to mind certain video shops of yesteryear which would display a small selection of benign movie “standards” for sale at the front of the premises, fig-leafing the store’s true purpose.

The Forbes article interviewed more than 50 college students who are subscribers to Chegg Study. The students interviewed represent a cross-section of institutions ranging from small state schools to top private universities.

Nearly every one of the students interviewed admitted that they use Chegg Study to cheat on tests.

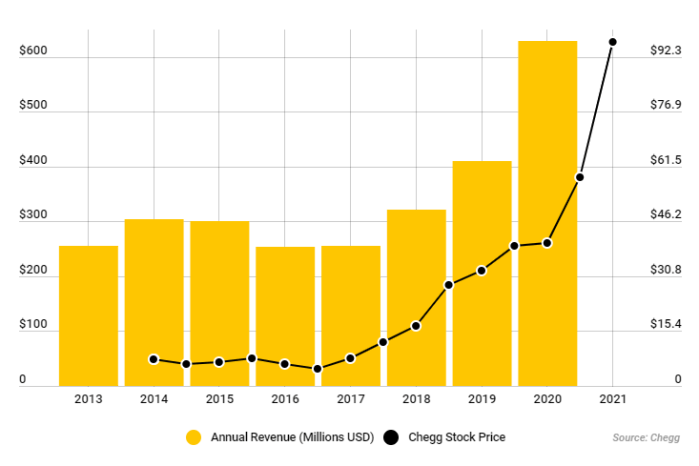

To view Chegg’s financial numbers is to notice a direct correlation between the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic — when education went virtual practically overnight — and a spike in revenue growth at the company. Quarterly revenues over 2019 have leapt 70% or more, and Chegg’s shares are up nearly 350% since the education lockdowns began in mid-March.

The company is now valued at a cool $12 billion.

The company is now valued at a cool $12 billion.

Corporate spokespeople deny that Chegg is taking advantage of the current situation to juice its sales and profits. Company president Dan Rosensweig contends that Chegg is the equivalent of an “asynchronous, always-on tutor,” ready to help students with detailed answers to problems.

On-demand education, if you will. Or a student version of the GE Answer Center.

But the “new reality” of virtual education and Chegg’s role within it brings up a number of concerns. As cheating becomes easier to do and hence more prevalent (human nature being what it is), what happens to the value of a high school or college degree? Can degree credentials mean as much as they did before?

It depends. For some jobs where the ability to find accurate information quickly is important, finding someone who mastered the function of “chegging” while as a student might actually be the better candidate for the position. On the other hand, if the position requires a person who will uphold the highest ethical standards at all times, that same candidate would be the wrong one for the job.

Ultimately, it’s the students themselves who will likely be the victims long-term, because if they “skated on through” during their school years and didn’t actually learn the material, that will soon become evident when they go into the workforce. “Find out now … or find out later,” one might say.

Looking at the other side of the coin, how can schools make sure that they’re monitoring and mitigating cheating effectively, such that employers can be confident of the comparative value of a degree from one school versus that of another?

There are a variety of “remote proctoring” surveillance tools like Examity and Honorlock that can lock students’ web browsers and observe them visually through their laptop cameras. While on paper these look like effective (albeit costly) ways to crack down on online cheating, the degree of their actual success is debatable.

Some respondents in the Forbes student interviews reported that they “chegg” their online tests regardless of whether or not they’re being proctored, citing the belief that if they aren’t using the school’s own Wi-Fi connection, it’s impossible to detect the cheating activity.

Furthermore, anecdotal reports from teachers in my home state of Maryland state that on test-taking days, often there are large spikes in the number of students who mysteriously run into “problems” with their Zoom connections – and hence are unable to be observed while taking their tests.

But the issue goes even further – to the very heart of the notion of virtual learning itself and whether distance learning is ill-serving young people. Some students have found it hugely challenging to be skillful learners in the “virtual” world. A business colleague of mine shared one such example with me:

“Someone who I respect greatly and consider to be an honorable man has accepted his son’s cheating, since he went from being an ‘A’-student to failing because he couldn’t handle online learning. He was a visual and auditory learner and without those two things, the information wouldn’t stick.

The student and his dad talked about the 12 consecutive chapters he was supposed to be reading. When the father was satisfied with his son’s understanding of the material, he allowed his son to do whatever was necessary to get through the tests.”

When the situation gets to the point that students’ own parents are going along with the cheating, it means that we have an issue that goes way beyond one particular company that’s taking advantage of the dislocations in the educational arena while laughing all the way to the bank. At its root, the problem is virtual learning and the way it’s being structured.

Of course, the coronavirus crisis built quickly and took many colleges and school systems by surprise — so the fact that jury-rigged ways to deal with the virtual learning have fallen well-short expectations is completely understandable. But the shortcomings have become so glaringly obvious so quickly, new creative thinking is obviously needed – and fast.

If you have thoughts or ideas about steps the educational field could be taking to solve this dilemma, please share them with other readers here.

Considering that the digital revolution has dramatically improved access to information pretty much across the board, while also lowering the price of delivering the content to consumers, doesn’t it seem like college textbook publishing has been operating in something of a time warp?

Considering that the digital revolution has dramatically improved access to information pretty much across the board, while also lowering the price of delivering the content to consumers, doesn’t it seem like college textbook publishing has been operating in something of a time warp?